The Making of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Thank You for the Dance’

By Triple R volunteer writer Katherine Smyrk

‘Another record of songs also might emerge, but one never knows,’ said Leonard Cohen in the promotion for his album You Want it Darker.

Leonard died on 7 November 2016, aged 82, just 19 days after the album’s release. It seemed remarkable and also deeply appropriate that the inimitable Canadian songwriter/poet/musician was making critically acclaimed music right up until he died.

But, in fact, it went beyond that. Three years after his death, Leonard Cohen’s 15th album, Thanks for the Dance, has been released. It’s not a posthumous reflection on his life’s work, a nostalgia-fest of B-sides and live recordings. It’s a whole new album, with fresh material he recorded with his son, Adam Cohen, right before he died. This remarkable work was an easy choice for Triple R’s Album of the Week.

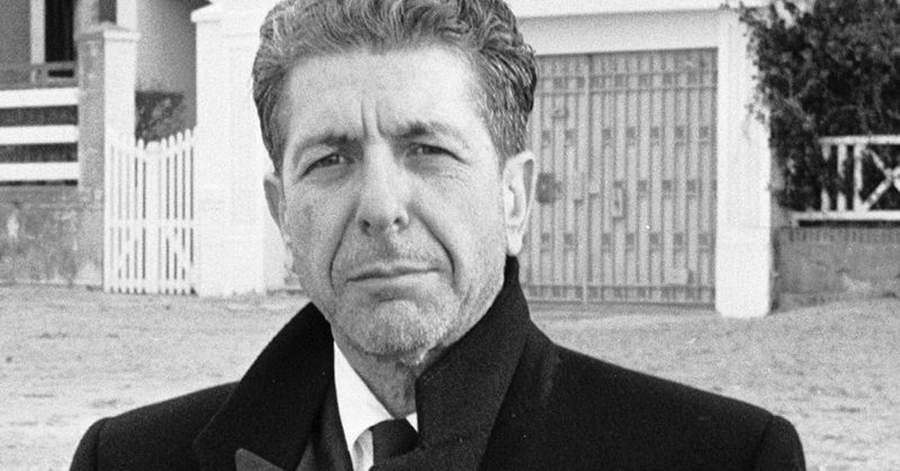

Leonard Cohen in 1988

Photo by Roland Godefroy via WikiMedia Commons

With the help of recording engineer and mixer Michael Chaves, Adam helped his father lay down a number of extra tracks during the recording of You Want it Darker, and has spent the years since Leonard’s death carefully and tenderly turning those recordings into an album.

‘They’re a continuation,’ Adam told The New York Times. ‘Had we had more time and had he been more robust, we would have gotten to them – sadly, the fact that I would be completing them without him was given.’

To help render these tracks the way his father wanted, Adam recruited a slew of remarkable musicians, such as long-time Leonard Cohen collaborators Jennifer Warnes and Javier Mas, along with the likes of Beck, Feist and Damien Rice.

‘There’s that Jewish tradition of bringing a tiny rock or stone to a grave site,’ Adam said. ‘I felt like every person was there to just humbly deposit their little rock near the engraving of his name.’

But it wasn’t a straightforward process, creating an album out of the snippets, thoughts and intimations of a musical legend who had died years before.

As recording engineer and mixer Michael Chaves said in a promotional video for the album, ‘At first it seemed quite easy, because we knew what he liked. It’s just the deeper you get into it, you second-guess yourself.’

It was meticulous work at times. For the final track, ‘Listen to the Hummingbird’, they actually tracked down a recording of Leonard reading the poem at a promotional event for You Want It Darker. They carefully edited out the background noises of halogen lights and people shuffling, and rendered Leonard’s haunting baritone like it was recorded in a studio, cushioned by delicate piano.

Adam had to spend endless hours listening to his father’s voice while processing his own grief. He said it took him about seven months before he was able to listen to any of the things they’d recorded.

‘I still can’t believe that I don’t have that source of wisdom to consult, and that I have to have imaginary conversations sometimes rather than real ones,’ he told The Guardian. ‘But mostly it’s just a case of missing one’s old man.’

The result, though, is a beautiful final farewell both from Leonard Cohen and to him. But don’t be mistaken – this is not a depressing dirge of an album. There are tracks that make you want to weep on your knees, but it also sparkles with Leonard’s trademark wit, wordplay and astute observation.

‘It doesn’t feel like a museum exhibition, it feels like a living, breathing, work of art,’ says Leslie Feist in the album’s promo video. ‘At the time that he sang these he knew he wasn’t going to be alive for very long, and with all of that lifetime of truth-telling, soothsaying, he presents these new ideas that are very much about living, they’re not about dying.’

When Javier Mas first put on the headphones to listen to Leonard’s recordings, he started crying. He turned to Adam and said, ‘I really thought I’d never get to play with your father again.’

As for choosing the name of the album, that came easy to Adam: ‘Thanks for the dance. Thanks for the dance of life. Thanks for the highs, the lows, the sweetness, the bitterness, the tragedy, the comedy, the beauty, the sourness, the lightness. That’s what he would have called it. That’s what he referred to it as, this dance, how lightly we’re all here.’

Katherine Smyrk is a Melbourne-based writer of fiction and non-fiction, and the Deputy Editor of The Big Issue. When she's not reading or writing she is usually eating cheese, playing footy or dancing to Beyoncé. You can follow her on Twitter.