Deeper Read: How Triple R Made Remote Broadcasting Happen

The coronavirus outbreak prompted Triple R to devise a way for broadcasters to present their shows live from home. It took Triple R’s technology team three weeks to build the system. But what is the system? And how was it created? Technology Manager Cameron Paine explains the nuts and bolts of it all in glorious, nerdish detail.

INTERVIEW MIA TIMPANO

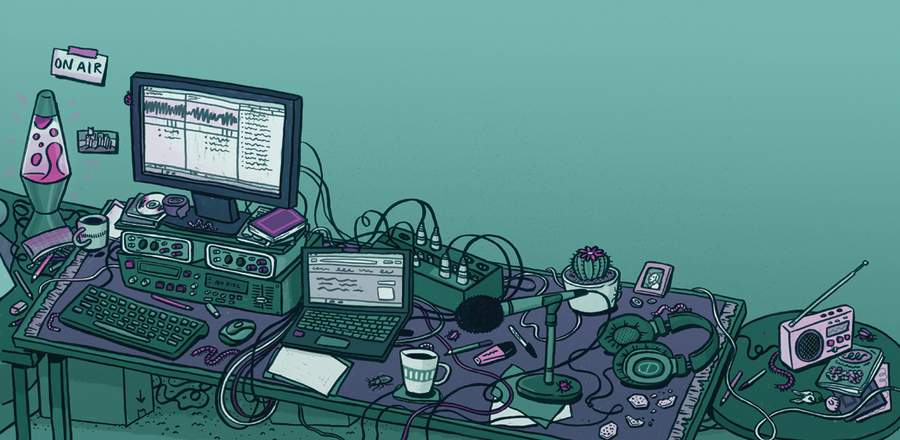

ILLUSTRATION ASHLEY RONNING

Illustration by Ashley Ronning

There was a time, not so long ago, when it looked like Triple R might not be able to deliver its regular programming. In the early days of coronavirus reaching Victoria, we didn’t know if or when a lockdown would happen. Nor could we anticipate what that would mean in terms of access to the station. We needed a system that would allow us to broadcast something remotely. Maybe not shows as we know them, but something.

In under a month, Triple R’s technology team devised a complete and fully operational remote broadcasting system. In essence, it allows any broadcaster to jump online, whack on a headset, upload a bunch of music files, and do their show from home. Or, indeed, anywhere in the world, provided they have an internet connection. The system also enables broadcasters to pre-record their shows, which play out from the same system. Plus, we can switch back to the station whenever shows are being produced in the studio, as per normal (with, of course, in-studio hygiene provisions and a maximum of one person per show per studio).

The result, from a listener perspective, has been a fairly seamless experience. But this has, in fact, been quite a technological feat.

Think about it. How do you replicate a live radio studio through the internet? And how does that remote signal (aka the music and the voices) produced by the broadcaster in their home then get broadcast as radio? And given that it’s all being sent to computers at our Technology Manager Cameron Paine’s house, what’s happened to Cam’s house?

The answer to this last question is: it’s fine, Cam’s just running a radio station from home; he has a space for hobby technology that he has repurposed for producing Triple R radio. For answers to the previous questions, we need to go to Cam himself.

Mia Timpano: Take us back to the earliest point at which we discovered that there might be a shutdown because of coronavirus. What was the technology department thinking at this point?

Cameron Paine: At the outset, the aim was to have curated playlists going to air from the moment we were told to no longer be in the building. The icing on the cake would have been having sponsorship announcements, because our revenue had been significantly impaired; to impair it further because we couldn’t meet our obligations seemed a bit like business suicide. And then maybe, just maybe, there was the outside chance we could get some kind of a live-presented Breakfasters happening.

Everyone on my team was clear about what the end-goal was and enthusiastically embraced the pieces of that work that I broke off and handed them. There’s been a lot of collaboration, but to a great extent we worked autonomously and produced this [remote broadcasting] thing.

I’m not entirely convinced that it’s as magical as everyone thinks that it is; it’s pretty perfunctory. And the only reason we were successful [in getting it up and running within three weeks] is because [Station Manager] Dave [Houchin] gave us the latitude to work exclusively on this; if there weren’t flames licking out of something, then we could ignore all of our regular work.

I have to say: that’s a bit of extraordinary fun. It was pretty high pressure. But the bar that we set ourselves initially wasn’t stupidly high. And it seemed from the get-go that it was achievable from what we had lying around the station. All that was needed was people to roll up their sleeves and get to work – and we did that.

Within the first week, we’d achieved what we wanted with the exception of [a live-presented] Breakfasters. I said to Dave, “Look, to do Breakfasters, I’m going to have to spend a small amount of money because we don’t actually have everything we need in the station to make that work.” I got the impression Dave thought, “Why are you bothering to ask about this in the scheme of things?”

Our friends at Mannys sourced this piece of kit [that we needed to enable a live-presented Breakfasters]. I went and picked it up on a Saturday, so that must have been eight days from when we started on the project.

Within a week, it was obvious we could do live presentation and playlists with sponsorship – and it was only a tiny leap then to say, “Well, what if people want to pre-record [their shows]?” That’s kind of a variation on playlists with sponsorship. Basically, we’re playing media from stored files in a particular sequence that makes sure that our sponsorship obligations are met, and whether that pre-recorded material is something Julia Jacklin recorded in a studio last week or Monique Sebire recorded in her bedroom yesterday, it’s largely irrelevant to the technology that’s going to bring that to the listener.

So what is the technology that has enabled us to keep broadcasters broadcasting from home? Talk us through the vision for the system – and then how you built that system.

What we’re doing isn’t vastly different from what the station is well-equipped and trained to do: an Outside Broadcast, or an OB.

This is something that we do two or three times a year: we go to a venue outside the station, we set up a modest amount of equipment and we make some radio. The most recent occasion we did that was in the Treasury Gardens during Balit Narrun; [Still Here co-host] Paul Gorrie was on air for two hours on a Sunday afternoon from the gardens.

So we have the equipment that enables us to do that. I think it’s probably not necessary to conceal the fact that all of this equipment is now located at my house; that’s for very pragmatic reasons.

We figured that if we got locked out of the building before we finished setting shit up, then whatever effort we put in was going to be completely wasted – so we knew it had to be a location outside of Triple R. I pitched to Dave the idea that I would take my camp bed over to Triple R, because, as you know, the only thing that would make spartan domestic living intolerable at Triple R is having to sleep on the Band Room couch. Armed with a reasonable bed, there’s a fridge, oven, microwave, beer, comfy chairs... But Dave wasn’t having a bar of that.

That would’ve been pretty insane, Cam, if you moved into Triple R.

Well, the thing is that I would have been socially isolated. We were looking at the worst-case scenario that the government might play to keep a lid on this thing. But Dave was saying, “If you’re going to be isolated, you need to be isolated with your wife, which means that you need to be at home.” So we got past that.

I said, “Well, that means I need to take all the shit home. Because if we don’t actually finish the preparations before we’re denied access to stuff, and if I’m isolated, I can continue working on this. It might take a bit longer if I don’t have [IT Support Specialist] Jack [Knight] giving me a hand, but while I’m isolated, I can keep working on it.”

That’s how we arrived at the conclusion that it needed to go to my place. And so really what we set about to do was set up an OB from my house.

What equipment is involved?

There needs to be a mechanism to connect the station to the OB location. Broadly in our industry, we call this “linking”.

About five or six years ago, we invested in a digital device that enables a whole different array of mediums that we can use to get the broadcast content back to the station. This thing is called a codec. It has a peculiarly technological name that has a mishmash of letters and numbers; it’s made by a company called Tieline. [The device’s] friendly name, if you like, is Merlin.

So, we have a pair of Tieline Merlins, one that lives permanently at the station, and one that we take out to the Treasury Gardens, for example, if we’re going to Balit Narrun. I brought the one that we would normally take – the field codec, as we call it – back to my place.

With that codec, we have a special arrangement with Telstra. Many broadcasters do. Telstra segregates a small portion of their mobile telephone network for broadcasters to use. This makes broadcasters immune from the MCG effect.

What’s the MCG effect?

If you take your phone to the MCG on Grand Final Day and try to give your sister interstate up-to-date information about how the footy match is going, you will fail, because there are 100,000 other people trying to use their phones at the MCG.

Telstra, recognising this and recognising that broadcasters often want to broadcast from places like the MCG and might want to use their cellular telephony infrastructure to do that, set aside a bit of their infrastructure exclusively for the use of emergency services and broadcasters.

So we have an arrangement with Telstra and we have a little piece of hardware that allows us to use that spectrum. I upgraded my NBN plan at home, so if my ISP for whatever reason breaks my NBN connection, we use the Telstra connection; if the local Telstra tower goes down, then we use my household NBN.

[Now, to recap,] we’ve got a codec at the station, we’ve got internet infrastructure in between, we’ve got a codec at my house.

Typically, one plugs a mixing desk into the codec, like the consoles at the station. In the studios we use a piece of software [Bowie] to play a lot of the music that people bring into the station on their USB sticks, so I set up a computer to run that software.

Normally, we have no use for software that does automatic playout, though it’s part of the software that we bought for our studio upgrades a couple of years ago. We had that capacity, we’d just never utilised the capacity, so we enabled it.

[Music Coordinator] Simon Winkler and his colleagues in the programming team, Sam [Cummins] and Adam [Christou], came up with around 33 hours of music. We figured that was enough to get us going, and then we would add more material to it and take material away.

That material enabled us to suspend our live-presented Graveyard Shift programs [hosted by a rotating roster of 180 dedicated broadcasting volunteers]. It’s very, very important that we reduce the risk to our volunteers of exposing them to the virus, and the consequences for their families and friends, so Dave was very keen that we shut that down.

That automated music has really only ever been used for The Graveyard Shift. Whereas in our original thinking of what we wanted to deliver quickly [based on the assumption that] there’d be no talking on the radio and no access to the studios, the starting point was that pool of music.

So now, we’ve got the computer that plays that music. It can play it when people push buttons or when a computer says, “Go to the next track.”

Can you explain how that’s triggered?

Let’s circle back around to the mixing desk.

In our studios, our mixing desks have got buttons and faders: faders that raise and lower the level of the audio, and buttons that start and stop the audio.

If that fader is controlling a source, like a CD player, when you press the on button, the CD starts playing. When you press the off button, not only does the sound extinguish but the CD stops playing.

So I needed a mixing desk for someone who wasn’t physically in my house to be able to do that. One of the options we considered early on was that I would push the buttons and broadcasters would speak and select the music. Obviously that’s not sustainable; I’m a single human being.

Remember: we were looking at extreme scenarios just to get the ball rolling. I was saying, “If we want live-presented Breakfasters every day, that’s a three-hour impost on my day, to be sure, but if I’m in isolation in my house, there’s a lot of my ordinary work that I’m not going to be doing every day.” So that wasn’t as preposterous as it sounds now.

That was one of the scenarios that we kicked around. While we agreed that that wasn’t sustainable for anything more than one program a day, that would have meant that we could have one program a day on air. Which comes back to the magic piece of equipment and the money that I needed to spend.

I’ve known that remotely controllable mixers exist, but I never really explored the flexibility of how remotely controllable they were. So I found a device that was remotely controllable over the internet.

As I said earlier, our friends at Mannys had one in stock – not in their Fitzroy shop where we would ordinarily go, but they were happy to ship it interstate for us and allow me to try it out to see if it would work on the basis that if we liked it, we would purchase it.

After half an hour, I had no thought of returning it to them. It delivered more than I had gleaned from the documentation I read before we purchased it.

So, the remote panel – this is the one broadcasters bring up in their browser window at home?

Correct. It’s got some faders and it’s got some buttons on it.

The brain behind that that does the actual mixing is what we bought from Mannys. It’s a lump of hardware – the thing [that you can see in the picture] with lots of wires all plugged into it.

So now, we’ve got a mixing desk, we’ve got sound sources, and someone outside my house can control these things. We’re looking pretty good at this stage, and still there’s not total lockdown.

The other thing we struggled with, at least conceptually, is the problem of getting a live presenter’s voice back to the station. The way that this would be conventionally solved by the broadcast industry costs money because hardware needs to be bought, but is also predicated on having an operator back at the station mixing the voices together with the console. I considered that for about 20 minutes and thought, “Nah. We’re going to need to step outside the way the broadcast industry would solve this.”

I looked to the kinds of audio conferencing tools that most people are familiar with, like Skype. We settled fairly easily on Skype. Its competitors were disqualified for either reasons of quality or latency or complexity.

Whatever we put together, we had to be able to train people to use it effectively. In my mind all along has been trying to create a workflow experience that is not vastly dissimilar to what you would do if you came to the station. Obviously, you’re not in the station, so we had already interposed a huge obstacle, but I think that once you get your head around the various components and how they interact, you can very quickly get into the same kind of a rhythm that you would sitting in the studio at Triple R.

So, we’ve got our two computer sound sources: music and voice. We’ve got our remotely controllable console. We’ve got our Merlin codec at my house. We’ve got its cousin at Triple R, and there’s a switch in our master control at Triple R that makes sure that this stuff can go to the transmitter.

Currently, we’ve got that switch set up so that whatever comes from my house appears on the outside broadcast channel on each of our three studio consoles, which enables us to dovetail content that’s being produced in my house with content that’s being produced still in the station. And that’s the dry chapter and verse of it all.

What has your wife Justine thought of it all?

It’s really an extension of her tolerance of living with me. Because I am a nerd and she knows that. She’s known that for decades. She supports my work at Triple R and at Peebs [PBS] at a very deep level; she’s as committed to community media as I am.

I actually heard her talking to her sister about “the radio station upstairs”, so I think she’s got a little bit of pride that we’ve got this essential piece of Triple R in the room upstairs.

Have you had conversations with technology teams at other community radio stations?

I’ve had many conversations. Most of those conversations have been with stations in our sector with a similar stature to ourselves: 4ZZZ in Brisbane, 2SER in Sydney, and Peebs.

There’s a good degree of collegiality and ideas-sharing between all of us, but we are serving different internal cultures. So an appropriate way of solving the problem for Triple R does not necessarily map to the other stations. And the stuff that each station had in the cupboard when the WHO declared “pandemic” and governments started to respond is quite different.

Most technologists would go, “Well, what have we got in the cupboard?” Because the fewer things we need to buy, not only does that reduce our cash-outlay, but it eliminates any potential supply chain issues.

I think we all looked at how each of us was solving the problem and went, “Yeah, OK, I see why you’ve done it that way. That should work.” Rather than, “Oh, you did it that way. Can I copy what you’ve done?” Although that wouldn’t have been a problem, but it’s been more words of encouragement to each other, rather than handing around blueprints of how to solve this problem. Because the problem we’re trying to solve – allowing people who broadcast to do so safely during the pandemic – is quite different for different stations. And the resources that each station could marshall to solve those challenges are quite different. Therefore, the differences in the solutions that the stations have come up with reflect the difference of inputs.

What aspect of the project are you proudest of?

The fact that we took the original idea so much further than anyone believed was possible, and we had all of those elements functioning within three weeks. We’ve shown that when push comes to shove, as a collective we can get in there and get shit done.

There’s no single element that I’m proud of; I’m proud of the output. To sit back, as I did last Saturday, with a beer, listening to the tail-end of Brian [Wise]’s show and the two hours that Annaliese [Redlich] put to air without my hands being anywhere near the technology, you cannot believe how enormously satisfying that that is.

I often sit in my armchair at the back of the house on a Saturday, listening to Triple R or to Peebs – the fact that all that was going on remotely controlled from the room upstairs was largely irrelevant. I was able to completely forget that there was a shedload of gear upstairs that was making that happen. And if it weren’t for the self-conscious or gleeful utterances from the broadcasters that they weren’t broadcasting from the station, I doubt that many of our listeners would know.

This article first appeared in our subscriber-only magazine, The Trip. Mia Timpano is editor of The Trip, Triple R's content and communications coordinator, and host of Requiem For A Scream. Ashley Ronning is an artist, illustrator and music enthusiast. She has watched too much Jeopardy in lockdown.